I am a teacher. And despite what you have probably seen and heard over the last few days, I am not a hero.

When I was younger, I wanted to be Wonder Woman. I grew up watching the Super Friends cartoon on Saturday mornings, and Lynda Carter on weekdays after school. Even as I sit here, many years older and wiser, there is still something about superheroes that captures me. I’m not sure what it is…I mean, let’s face it, Lynda Carter’s Wonder Woman was not exactly a badass. But how awesome would it be to beat the crap out of 20-30 criminals at once while not breaking a sweat or messing up your hair?

Despite the fact that I manage groups of 20-30 teenage students at once for several hours a day without breaking a sweat or messing up my hair, I am not Wonder Woman. In fact, if I were a hero, it certainly wouldn’t be Wonder Woman. I’ve always thought that I’m really more like Batman – I run around with a bad attitude doing what I think is the right thing, regardless of the specific orders of those in authority, and as a result, I’m constantly being chased by people who think I am a criminal. But alas, I am definitely not a hero. I am a teacher.

I go to work every morning thinking, “I will be nicer today than I was yesterday.” But almost as soon as the day starts, I am reminded that I am expected to function in a system with which I do not agree. So I go rogue. I do what I think is the right thing. I attempt to educate my students while ignoring the newest directive from the bureaucracy. I fight off the angry emails from parents who are disgusted by my “behavior.” I listen to the whining pleas of jaded teens, who want to maximize their grades but only at the end of the quarter when it’s too late. I go home from work every afternoon thinking, “I’m a stark-raving bitch.” Rinse and repeat. This is me. This is what I do. I am not a hero; I am just a teacher.

Enter: global pandemic. The spread of “teachers are heroes” tweets and memes is outpacing the exponential growth of the coronavirus itself. And it’s not just teachers…truckers are heroes. Grocery store workers are heroes. Delivery people are heroes. Small business owners are heroes. Parents are heroes. Generation Xers are heroes. Millennials are going to save us all; wait, no…GenZ to the rescue!

In the meantime, I’m still just doing what I do. Circumstances have changed, but I still wake up every day and think “I’m going to be nice today.” I still make my best attempt to function in a system with which I do not agree, and I still ignore directives if I think they’re ridiculous. This is me, and this is what I do; whether it’s in the virtual world or the real world. I am not a hero. I am a teacher.

And all of those other people on the list? They’re doing the same thing. They’re not heroes. They’re being themselves. They are going to work so they can afford to feed their families. Or maybe they are going to work because they’ve found a profession that they love, even though it might be difficult or life threatening. Many of them are dedicated, hard working, charitable people. But they are not heroes. There’s really nothing extraordinary about going to work every day and doing the same thing that you’ve always done, even if the circumstances happen to be extraordinary. A hero is not defined by the fact that he can adapt to a changing environment, nor is he defined by the fact that he does a job that no one else wants to do.

I am a teacher. Despite the difficulties that I face, it’s what I love to do. As much as I might aspire to be Wonder Woman, I know that I am not. Though it has taken some time, I have finally learned to let go of Wonder Woman and embrace my inner Batman…particularly given the fact that we both seem to share the same philosophy with regard to social distancing. But please stop calling me a hero. I fear that if you continue to project the image of “hero” onto someone who is merely adapting to changing circumstances, then you will be quite disappointed when the mask comes off and you see Bruce Wayne.

ing together. Whenever I have used groups in the past, there were always students who were not working, students having side conversations, and students who just did not seem to get along with those in the group. I wanted to do an activity that would model the ideals of good teamwork. Development of the skills required for effective collaboration takes practice. We are so busy trying to hit our content standards, that we don’t always recognize the value of spending time teaching “soft skills” such as communication and teamwork. As a result, these skills are often lacking in many professional working environments.

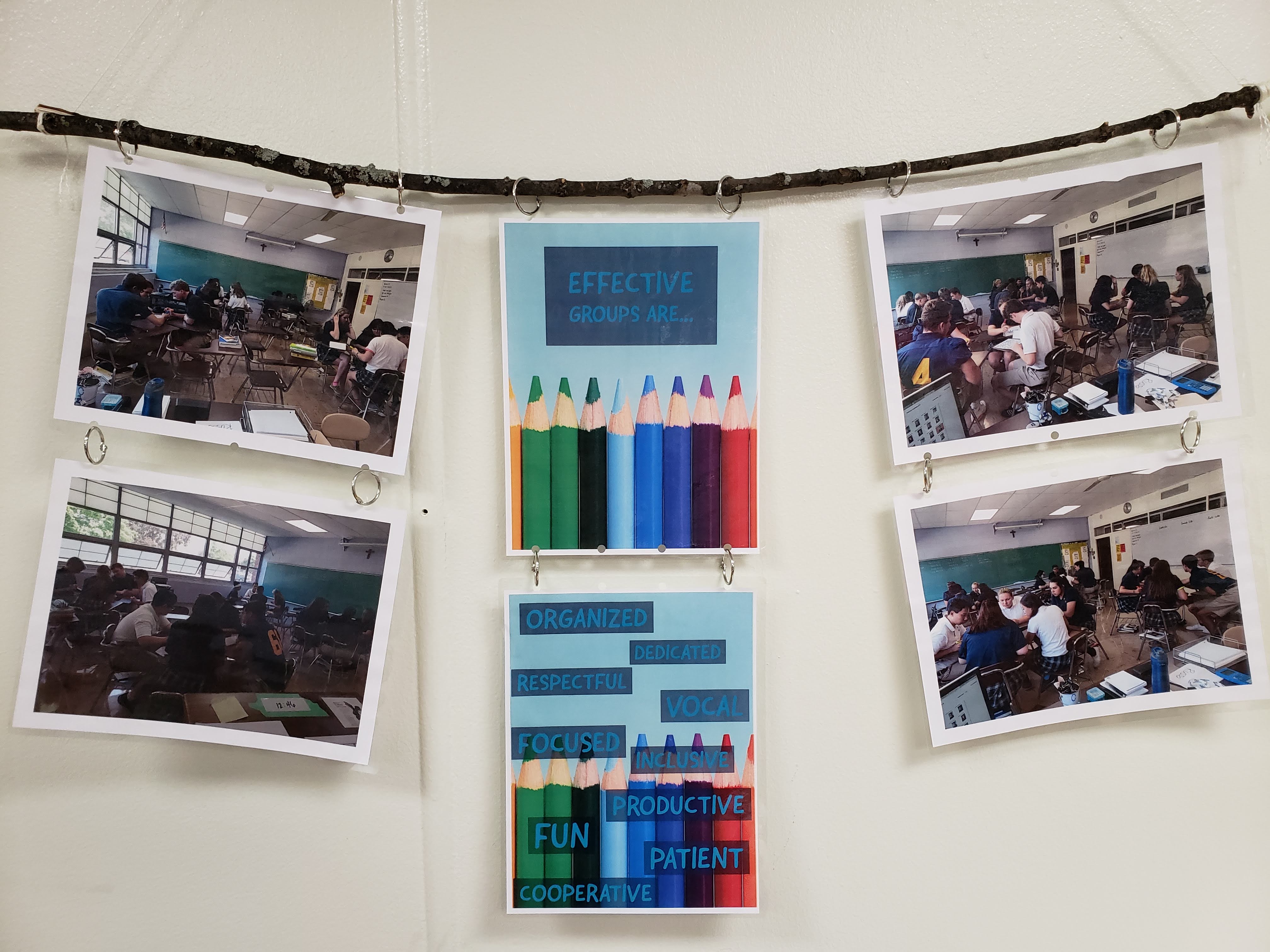

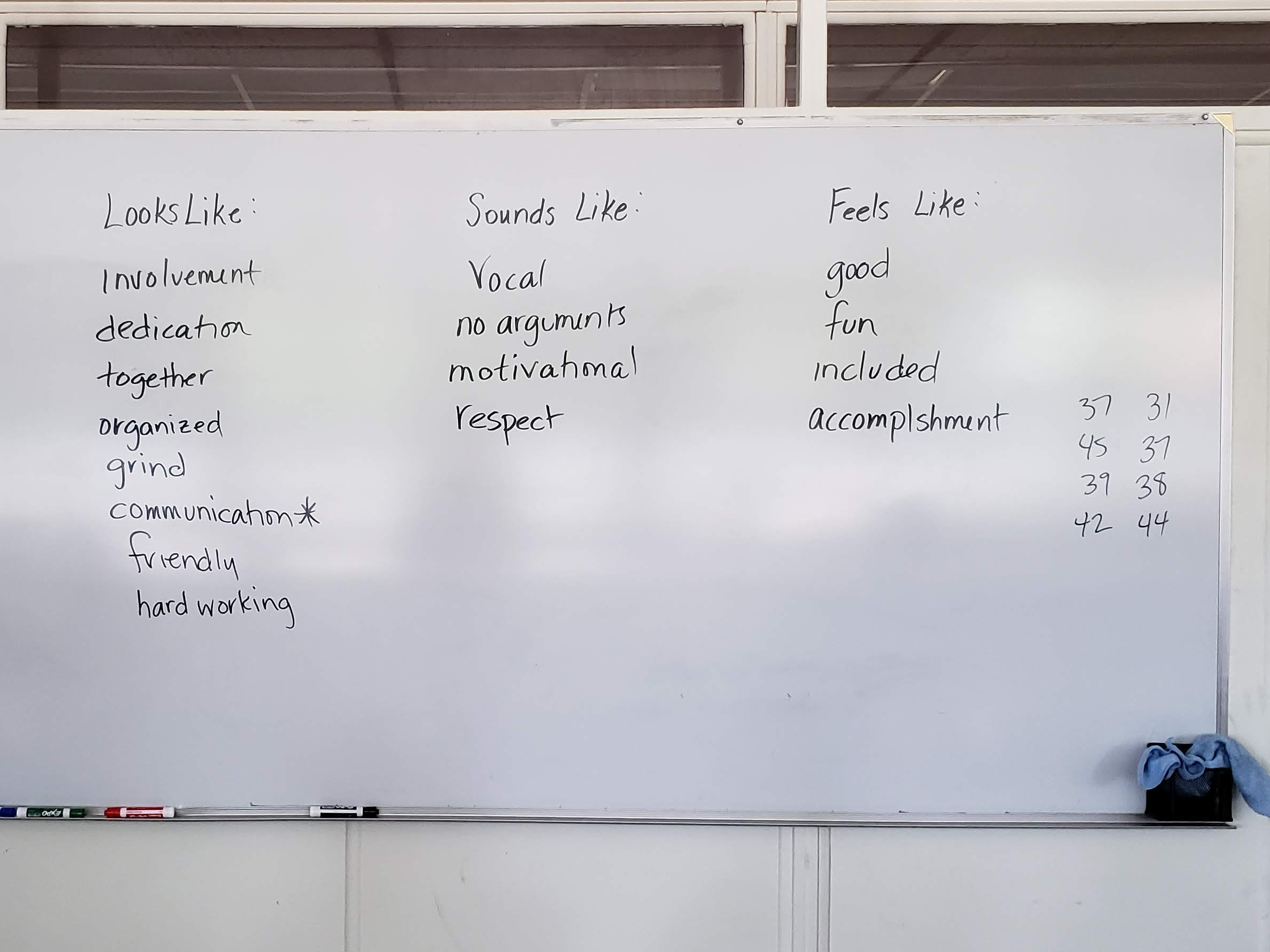

ing together. Whenever I have used groups in the past, there were always students who were not working, students having side conversations, and students who just did not seem to get along with those in the group. I wanted to do an activity that would model the ideals of good teamwork. Development of the skills required for effective collaboration takes practice. We are so busy trying to hit our content standards, that we don’t always recognize the value of spending time teaching “soft skills” such as communication and teamwork. As a result, these skills are often lacking in many professional working environments. After the second round, nearly all of the groups had improved. There was even one group that found all 100 numbers! I then had them make three columns on a sheet of paper. In the first column, I wanted them to write down words that describe what an effective group looks like. In the second column, I asked them to describe what an effective group sounds like. And in the third column, they were to describe what an effective group feels like. I let them talk for a few minutes, and then as a class, we had a quick discussion of the qualities of effective group work. I projected a picture of the class that I had taken while they were working. They were quite shocked that they did not even notice me taking pictures. I asked them if the students in the picture looked focused, determined, and engaged. It was clear that they were.

After the second round, nearly all of the groups had improved. There was even one group that found all 100 numbers! I then had them make three columns on a sheet of paper. In the first column, I wanted them to write down words that describe what an effective group looks like. In the second column, I asked them to describe what an effective group sounds like. And in the third column, they were to describe what an effective group feels like. I let them talk for a few minutes, and then as a class, we had a quick discussion of the qualities of effective group work. I projected a picture of the class that I had taken while they were working. They were quite shocked that they did not even notice me taking pictures. I asked them if the students in the picture looked focused, determined, and engaged. It was clear that they were. dents are walking through my door. Certainly they must know by now whether or not they are “good” at math – most of them are juniors and seniors in high school. They’ve never done well in a math class before, why would this one be any different?

dents are walking through my door. Certainly they must know by now whether or not they are “good” at math – most of them are juniors and seniors in high school. They’ve never done well in a math class before, why would this one be any different? and said,

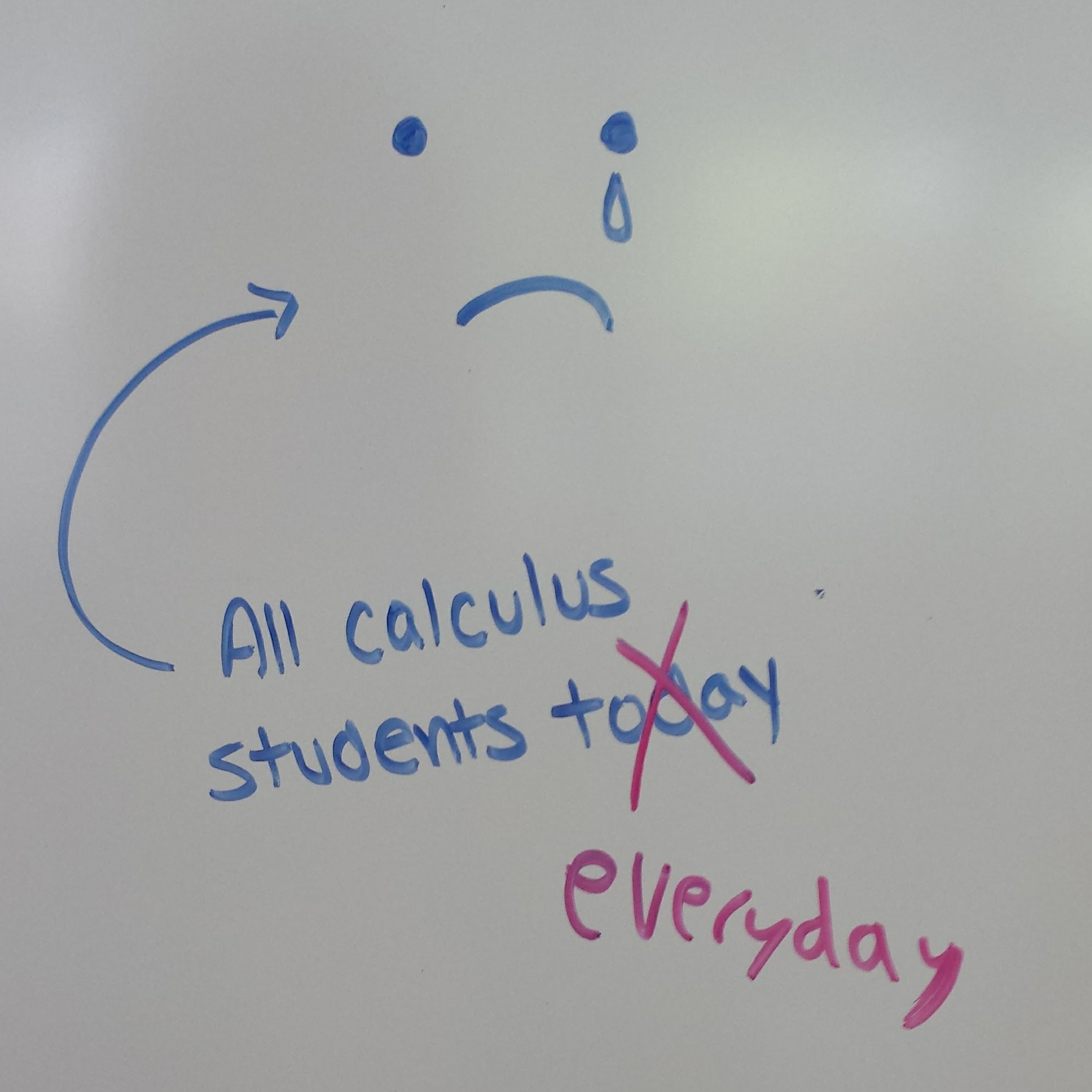

and said, Enter: AP Calculus. I am extremely hard on these students. On purpose. From the moment they walk in the door, they are pummeled with a big fat reality check. It starts when I give them each a packet of letters written to them at the conclusion of the school year by the previous AP Calc class. The letters usually describe horrors that these honors students have never dreamed they might experience. Last year’s students discuss their first failures, lowest grades ever, and how they might not ever understand math again. They talk about how Russo doesn’t grade (or check) homework and they fell into the trap of not doing it – even though they knew they probably should have. It is not uncommon for me to have several Calc students cry in my classroom because of their grades. They feel like they are rolling downhill with no brakes; and they have no control over where they are headed.

Enter: AP Calculus. I am extremely hard on these students. On purpose. From the moment they walk in the door, they are pummeled with a big fat reality check. It starts when I give them each a packet of letters written to them at the conclusion of the school year by the previous AP Calc class. The letters usually describe horrors that these honors students have never dreamed they might experience. Last year’s students discuss their first failures, lowest grades ever, and how they might not ever understand math again. They talk about how Russo doesn’t grade (or check) homework and they fell into the trap of not doing it – even though they knew they probably should have. It is not uncommon for me to have several Calc students cry in my classroom because of their grades. They feel like they are rolling downhill with no brakes; and they have no control over where they are headed.